Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga and ‘Mysore’ Self-Practice (Part 1)

Alan O'Leary writes:

At the Camyoga workshop in Insabina last year, and more recently in The Yoga Space (Leeds) I introduced the Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga system. The talk was intended for those with no experience of the system, but also for those who might have been studying it for some time. Talk around yoga tends often to be Chinese whispers, so I hoped to clarify a few basic facts about the structure and character of the Ashtanga system as well as to sketch some more controversial themes about its origins and relation to other forms. The talk was illustrated with photos and video, but I will try to give some idea of what I said in this and a couple of subsequent blog posts.

The talk had three parts:

- the structure and postures of Ashtanga yoga;

- ‘Mysore’ self practice and teacher adjustments;

- the origins of Ashtanga & related yoga traditions.

This post concerns the first part, that is, the structure and postures of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga. But I have to begin by mentioning Mysore self-practice straight away, because it’s considered to be the traditional, not to mention the best way to learn and internalize the system.

Learning Ashtanga the Mysore way involves studying with a teacher but, instead of following a class with everyone doing the same thing, the student will practice at her or his own pace, and the teacher will add a new posture when adequate ability is demonstrated in the previous posture. As one of my teachers, the very knowledgeable Mark Singleton (more of Mark later) once put it, this makes the six (yes, six) distinct series of Ashtanga into one long sequence. Most of us tend to learn and practice the primary (first) series in so-called ‘led’ classes, and the other series remain a dark continent, the visiting of which is postponed to our next incarnation. Studying the Mysore way, the student is much more likely to progress beyond primary, because of the individual attention from the teacher and because of her or his intimate familiarity with the student’s capacities and practice. Likewise, the series themselves may stop being perceived as distinct entities, but will be understood as flowing from one to the next, with postures being added on to primary from intermediate, and eventually to intermediate from advanced.

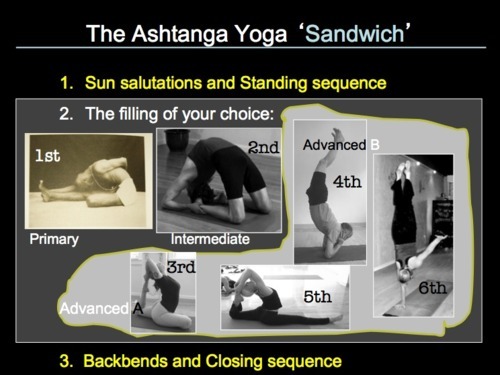

The famous practitioner David Swenson has used the term ‘Ashtanga yoga sandwich’ to describe how the practice is structured. By this he means that we always begin with the two sets of sun salutations, Surya Namaskara A and B, and then the standing sequence. Once the student has gained a basic proficiency the practice always finishes with backbends and then the closing sequence, which itself begins with the shoulder stand and ends in rest (sometimes referred to as Savasana). In between goes the ‘filling’ of the Ashtanga yoga ‘sandwich’: a set sequence of postures from primary, or from primary and intermediate, or just from intermediate, or from intermediate and advanced, or just from advanced (though, traditionally, only primary is practiced on a Friday).

As this suggests, at least officially, there are just three distinct series: primary, intermediate and advanced. But advanced contains so many postures that it has been itself been divided into four series, usually referred to as the third, fourth, fifth and sixth series (authoritative sources tell us that there were once only four distinct series – but that’s another story). Information about the series up to and including the fifth is fairly straightforward to come by, but I haven’t been able to discover the content of the sixth series (the one-armed handstand in the image above is speculation). The most comprehensively and systematically illustrated introduction to the postures of the first four series is Mathew Sweeney’s Ashtanga Yoga As It Is, published in an updated edition a couple of years ago – it’s a kind of bible, and certainly an invaluable resource. Supposedly, once the six series of Ashtanga yoga are mastered, you practice each on a different day of the week, beginning with second on Sunday and ending with primary on Friday (Saturday is traditionally a rest day).

Most of us spend many months or years working only on primary. For good reason: it conditions the body through a repetitive and severe (though addictive) regime of posture and movement. Primary focuses on forward bends – that is, it strongly works the hamstrings and back of the body even as it invigorates the internal organs. It also builds stamina through the linking movements (vinyasa), derived from the sun salutation, which connect the postures.

Given the challenge of all this, primary also conditions the mind by developing concentration, resilience and determination. As Beryl Bender Birch puts it in her book Power Yoga, if you practice first thing in the morning, nothing else you do that day will be as difficult.

How do you move on from primary to intermediate?

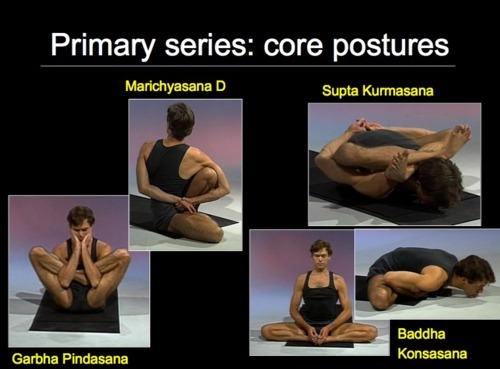

Well, the first condition of progress to the next series is being able to comfortably performing the full primary series and proficiency in all of its postures, in particular in what have come to be known as the core postures: Marichyasana D, Supta Kurmasana, Garbha Pindasana and Baddha Konasana, demonstrated here by Richard Freeman.

If you have this ability and proficiency you will have gained exceptional stamina and strength along with very open hips, a good lotus and excellent overall flexibility. Added to this, you are expected to be able to perform a ‘drop back’ on your own. This means being able to ‘drop’ from standing to full back bend, Urdhva Dhanurasana, and then stand back up again.

Sometimes a teacher who knows you well might allow you to progress to intermediate even if, say, your lotus isn’t great, but the other aspects of your practice are strong. You might have a knee injury that restricts you on one side, for example, and your teacher might judge that you are ready to move on despite that.

What happens when you progress to intermediate?

Once your teacher judges you to be ready to move on, he or she will add the first posture of intermediate (or call it ‘second’, as you prefer), Pashasana, after the last posture of primary, Setu Bandhasana. Postures will continue to be added as familiarity and proficiency grows, and the practice can get quite long (and tiring). Some teachers insist that you complete all of intermediate before being allowed to practice the second series on its own, i.e., without first practicing primary. Others take you as far as Karandavasana, over halfway through, and then allow you to ‘split’, i.e., to practice just the second/intermediate series without first going through primary. (A similar process occurs when adding advanced postures to intermediate, though in that case you leave out the seven headstands at the end of intermediate.)

After you ‘split’ and practice intermediate on its own you also omit some of the standing postures and move into Pashasana (the first posture of second) by taking a vinyasa directly after Parsvottanasana. (Some teachers prefer you to continue to do all of standing, or at least the tough standing balances.) No matter what series you are practicing you will first perform the sun salutations and the essential standing postures. These are: Padangusthanasa, Padahastasana, the two Trikonasanas, the two Parsvakonasanas, the four Prasarita Padottanasanas and Parsvottasnasana.

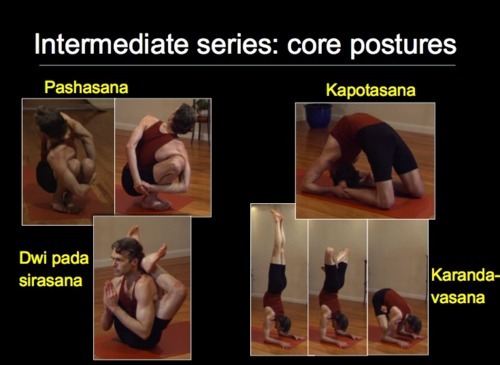

The intermediate series also has its core postures: those that most students find most difficult.

The first of these is the first posture of the series itself, the challenging squat/twist Pashasana. Then there’s the deep deep back bend Kapotasana; then the contortionist leg-behind-the-head balance Dwi Pada Sirsana; and finally, there is the lotus-plus-super-core-strength arm balance Karandavasana. Advanced practitioner Richard Freeman suggests that Karandavasana tends to require ‘at least two weeks of practice to master’. At least!

______________________

In the second part of the talk I dwelled a bit further on Mysore self-practice and teacher adjustments. I will summarize this and the third part of the talk in my next two posts.

Alan

a.oleary@leeds.ac.uk